A Richmond Firm Aims to Help Save the Planet by Cleaning Ocean Vessels With Robots

Ben Kinnaman thinks he can transform the shipping industry and the world's navies by making vessels faster, more fuel-efficient and cheaper to operate. In the process, he hopes to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and protect delicate marine ecosystems from invasive species.

How? By using small, autonomous robots to clean a ship's hull faster than was previously possible — at a fraction of the price. The robots were all designed and built by Armach Robotics, Kinnaman's new Vermont-based company. Its CEO and founder has extensive experience navigating the oceans, albeit thousands of feet below the surface.

Armach is a spin-off of Richmond-based Greensea Systems, which Kinnaman founded in 2006 to design technology used in the guidance of deep-sea robots. With more than 60 employees, Greensea works with the militaries of 16 countries worldwide, including the U.S., Canada, France, Saudi Arabia, Sweden, Turkey and the United Kingdom.

Now, Kinnaman has charted a new course into the realm of ship husbandry, or the cleaning and maintenance of oceangoing vessels. Specifically, Armach has developed a novel solution to an age-old problem.

"Once a ship becomes fouled, you start losing money hand over fist."BEN KINNAMAN

Biological fouling, or "biofouling," is the accumulation of marine life — algae, seaweed, barnacles, tube worms, mussels — on the surfaces of ships and nautical equipment. It's an enormously expensive problem, Kinnaman explained: Militaries and maritime companies spend $9.3 billion annually removing biofouling and repairing the damage it causes.

"Once a ship becomes fouled," he said, "you start losing money hand over fist."

Maersk Line, the Danish shipping company, has estimated that one of its container ships racks up $20,000 a day in excess fuel costs due to biofouling. A 2011 study done for the U.S. Navy found that biofouling increases the fleet's annual operating cost by as much as $1.15 million per ship.

The environmental effects of biofouling are equally massive. The shipping industry accounts for 3 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. According to a November 2021 report by the International Maritime Organization, the hydrodynamic drag created by a layer of slime just half a millimeter thick on a ship's hull can increase its greenhouse gas emissions by 20 to 25 percent.

The impact only worsens when the growth is left unaddressed. Five millimeters of barnacles or tube worms on the hull of a 320-meter-long tanker will increase that vessel's emissions by as much as 55 percent, the maritime organization report noted.

The problem of biofouling is as ancient as seafaring itself. In the fourth century BC, Aristotle wrote about the Echeneis, or "ship-stopper" fish of legend, that attached themselves to vessels and slowed or halted their progress like anchors. According to a 1952 report by the U.S. Naval Institute, later authors believed that Aristotle was actually referring to biofouling.

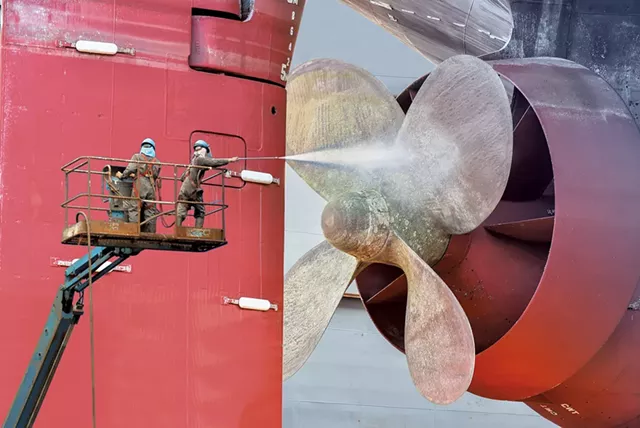

- COURTESY

- Shipyard workers cleaning a ship by jet water

Equally ancient are the methods seafarers have found to remove and prevent such marine growth. The ancient Greeks painted their hulls with mixtures of arsenic, sulfur, tar and wax. By the 15th century, the English were coating their ships with lead to prevent tube worms from burrowing into the wood. Still, many vessels became so befouled with barnacles and other marine life that they were no longer seaworthy.

Despite countless advances in oceangoing travel, Kinnaman said, modern methods of addressing biofouling aren't much better than those of centuries ago. In many respects, they're worse.

"We don't put anything as tame as arsenic and lead into [ship] coatings anymore. We put the nastiest shit known to man. It kills every organism that touches it," he said. "So we coat the ships, we scrape them down, and then we haul them out and repeat the process. It's insane."

The process of cleaning hulls and recoating them with biocides is expensive, time-consuming and environmentally destructive. Putting a large ship in dry dock keeps it out of commission for days or weeks. An alternative is to put divers into the water to manually clean a ship, but that can cost $35,000 each time, Kinnaman said.

Â

Even under the best of conditions, the process can be very damaging to marine ecosystems. Stripping layers of toxic coatings while a ship is in the water contaminates the ocean and transfers invasive species to new environments. Nevertheless, navies and shipping firms routinely perform these hull-grooming tasks, as often as monthly in cold waters and weekly in warm waters, to keep their fleets mission-ready.

Kinnaman readily admits that it wasn't his idea to take on the biofouling challenge. The 46-year-old native of Morehead City, N.C., grew up on the ocean. As a teenager, he had a job traveling from marina to marina scrubbing boat bottoms by hand in scuba gear, an unpleasant chore.

After getting his bachelor's degree in physics from Davidson College, in Davidson, N.C., Kinnaman worked for several years as a treasure diver in the Caribbean. But he soon realized, he recalled, that he was risking life and limb to earn fortunes for his wealthy patrons.

Kinnaman relocated to Baltimore and took a job building remotely operated vehicles used by the military in underwater salvage operations. He later earned a graduate degree in robotics at Johns Hopkins University and worked with movie director James Cameron to survey the Titanic wreck. In 2006, he moved to Vermont and founded Greensea.

When someone from the U.S. military called him in 2017 to ask if he'd consider applying for a federal grant to address biofouling using robotics, Kinnaman's initial response was, "Count me out."

Building autonomous robots that can accurately navigate the hull of a ship is incredibly complicated, he explained. As soon as the robot dips half an inch into seawater, GPS technology stops working. For an autonomous robot to do its job effectively, Kinnaman said, it must know exactly where it is on the hull at all times. He'd tried solving that problem eight times with other teams, without success.

Finally, with technical support from the U.S. military's Office of Naval Research, as well as ocean researchers at the Florida Institute of Technology and the University of Maryland, Greensea made a breakthrough. The company secured a Small Business Technology Transfer grant, which provides as much as $2 million in funding for the ongoing project.

Because Greensea isn't a robotics manufacturer, and Kinnaman couldn't find one that shared his vision for the project, he founded Armach Robotics in 2017. The company only emerged from its stealth mode and began publicly discussing its technology in March.

Armach now has 10 employees and a management team based in Richmond, with facilities in Plymouth, Mass., and Cocoa Beach, Fla. Once the company scales up, all of Armach's robots will be manufactured in Vermont, Kinnaman said.

- COURTESY

- An Armach robot performing hull maintenance on a ship

Armach's routine, hull-grooming technology prevents invasive species from gaining a foothold, much the way dental hygiene prevents cavities from forming.

"The concept is remarkably simple," he said. "We brush our teeth every day so that we don't have to have them pulled out every year and [new ones] put back in."

Recognizing that the technology had to be cost-effective and easy to use for the shipping industry to adopt it, Armach devised an autonomous robot that's about three feet long, weighs 60 pounds and can be deployed by one person.

Essentially, Armach offers shipping companies a subscription service. For a fixed monthly fee, Armach's robots, which reside on the ship, perform hull maintenance on the shipping company's own schedule, without the owner needing to buy or maintain the equipment.

When, say, a container ship arrives in port to unload its cargo, a crew member simply drops the robot overboard. Once it hits the water, Kinnaman said, the robot will "phone home" to Armach's operating center via cell, Wi-Fi or very small aperture terminal (VSAT) satellite communications.

Powered and connected to the ship by a tether called an umbilicus, the robot adheres itself to the hull using suction and traverses it in repeated horizontal passes, like a lawn mower. It scrubs the hull clean of marine life using rotating and articulating brushes. An Armach technician monitors the entire process remotely, though the robot uses artificial intelligence and sonar imaging to orient itself on the hull. Its positioning is accurate to within six inches.

The robot doesn't just clean the hull, Kinnaman said. It also gathers critical intelligence on its condition. With each pass, the robot builds a high-resolution map of the hull's surface using video and sonar equipment, inspecting and documenting any damage or defects.

Once the job is complete, Armach sends the ship's owner a detailed report, complete with analysis and comparison to previous reports. Armach can even schedule needed maintenance through its own network of service providers.

While the company currently focuses on servicing large oceangoing vessels and naval fleets, Kinnaman's long-term vision is to scale down the technology for high-end yachts and smaller recreational watercraft. Eventually, the system could also be adapted for use on such structures as offshore oil rigs and bridge supports.

And, because biofouling is also a problem in fresh water, Armach's technology could one day help to remove algae and zebra mussels from passenger ferries and water-intake systems in Lake Champlain.

Early adopters of Armach's technology declined Seven Days' interview requests, citing the proprietary nature of the project. Kinnaman said that Armach is currently working with the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps, as well as other sectors of the maritime industry, to perfect the technology. Aside from the federal grant, he noted, all of the investors funding Armach are based in Vermont, where he intends to keep the company headquartered.

The International Maritime Organization has set a goal of halving emissions from the shipping industry by 2050. Though Kinnaman was initially averse to wading into this issue and cleaning boats again, he now seems passionate about it.

"It would be awesome if everybody in the world could afford a Tesla, but that's not gonna happen," he said. "But here's an industry that could ... take a ginormous bite out of its worldwide carbon footprint, all the while saving money. Holy shit! We can do that.".

Article by:Â BYÂ KEN PICARD